|

2411 B Charles Boulevard Greenville, North Carolina 27858 or Post Office Box 154 Greenville, North Carolina 27835-0154 |

Phone:

(252) 757-3977 Fax: (252) 757-3420 email: hughcox@hughcox.com |

North Carolina Bar Number

6567 Department of Veterans Affairs Accreditation number 8925 |

|

|

|

The information contained in this website is general legal information and not legal advice on any legal subject. It is no substitute for the services of a

competent professional attorney experienced in these matters. This information is subject to change at any time due to new legislation or new court cases.

Veteran Stories and History: Recollections of being in the Military

World War II

![]()

![]() A Leaf from

this Chaplain's Diary (1944) by Rev. Oscar B. Wooldridge

A Leaf from

this Chaplain's Diary (1944) by Rev. Oscar B. Wooldridge

![]() The 11th Airborne Division enters Japan (1945) by Hugh D.

Cox

The 11th Airborne Division enters Japan (1945) by Hugh D.

Cox

![]() Sergeant Major John Diffin, 82d Airborne Division (1944) By Hugh D. Cox

Sergeant Major John Diffin, 82d Airborne Division (1944) By Hugh D. Cox

![]() An

Official History of the 441st Counterintelligence Corps

An

Official History of the 441st Counterintelligence Corps

Korean War

![]()

![]() An

Official History of the 441st Counterintelligence Corps

An

Official History of the 441st Counterintelligence Corps

Vietnam War

![]()

![]() An Unexpected Visit to Khe Sanh Hill 910 (1968) by Hugh D. Cox

An Unexpected Visit to Khe Sanh Hill 910 (1968) by Hugh D. Cox

![]() An

Official History of the 441st Military Intelligence Detachment

An

Official History of the 441st Military Intelligence Detachment

![]()

A Leaf from this

Chaplain's Diary

The Reverend Oscar B. Wooldridge was a Navy Lieutenant and

U.S. Navy Chaplain in 1944 assigned to the Mojave, California U.S. Marine

training area. Later, he spent many years as a faculty member and campus

Chaplain at North Carolina State University in Raleigh until his retirement.

There are thousands and thousands of "State" students who knew and know him

personally. They (actually, "We") are still influenced by his wise and

faithful advice and fatherly counsel. His 1944 diary entry appears below:

"It was shortly before midnight and I walked down, a long corridor of six connecting coaches to try to tell several hundred enlisted men and officers good-by. They were headed overseas. Mojave is not much of a place, but it is a station you grow to love and hate to leave. These men did not have a chaplain going with them, and I would, have given anything to have been one of their number. Some of them never went to Church, some were not saints morally or spiritually, but they were men with souls harboring part of God Himself, with potentialities of becoming like Him leaving home and family and the States to make a hazardous visit to the South Pacific.

There was Joe Luck, a Catholic boy, and a good pilot, who had narrowly escaped a plane crash about two or three months ago. We would kid each other about our difference in religious faith, even when he was recuperating in the hospital earlier this summer. But last night when we shook hands, his "say a couple of prayers for me, Padre" betrayed a deep sense of sincerity. And there was Bob Holmes, another Second Lieutenant, and Communications Officer for one of the squadrons. We had worked together on the Board of Governors of the Officers' Club. It was one of those instances when two fellows just seem to "click" Bob and myself. I'll never forget that ,day at chow when we discovered we were both brothers in the Phi Delta Theta national social fraternity. From then on it was "Brother Phi"!

In the next coach were the enlisted men, the greatest fellows in the world. These Marines, rating from MT Sgt right down to a "buck" private. The lump in my throat began to grow a bit as I recognized one of the mess men at whom we would yell when the soup was cold. If he did anything wrong at chow, the officers never failed to let him know it, but rarely did he ever get credit for doing something right. Officers are that way sometimes. With a fake smile on my face I shook hands with him saying, "Davis., I'll never forget you after all that poor chow you've dished out to us". Even if he heard me, the smile the smile he returned was a fake also. This was no time to smile. Inside every last one of those kids was a heart full of sorrow, sliced with a bit of fear. Out of all those men, only four ventured to lift a tune and appropriately enough they were singing, "Show me the way to go home".

There was a member of the Chapel Choir sitting in an aisle seat, but song was far from his lips and heart. Across from him sat a Private about thirty years old wearing handcuffs. Poor devil, he loved democracy and freedom, but he loved his wife and two kids more. He had refused to go, so the chains became necessary. He had a lot more to fight for than a single man, but he also had a lot more to lose. It's hard enough to ship over when you are leaving little ones behind, and at is much more difficult to be shipped over as a handcuffed prisoner with a court martial tacked on your record book. That's the kind of a fellow that never gets back.

My little speech sounded more hollow than ever by the time I reached the last coach. "This squadron is made up of such a good bunch of officers and men, the Marine Corps doesn't think you even need a chaplain." Probably it was the poorest sermon I ever preached as well as the shortest. Thank God for that blonde kid who saved the day by saying aloud, "I appreciated your sermon in the Chapel this morning, Chaplain. It was great". Come to find out ten of those lads within the space of a few feet attended the Protestant service that morning. For the life of me I couldn't remember having said much these men could carry with them into battle, but I hope it was due to my poor memory.

Yes, war is hell, it is not a game of football. Conditioned mentally and physically, these young thoroughbreds were heading west to participate in an International Olympic where the stakes are life and blood. The train upon which they departed was a modern invention, but the cause for their going was an antiquated outmoded method of solving the problems of human relations. For the amusement of what gods does one nation pit its youth against another until, by the process of elimination, the victor lifts his bloody head above the vanquished?

It may have been my melancholy mood. It may have been my attention was absorbed by another familiar face. It may have been I was so confused I didn't care. Yet, the train began to move before I was aware of it. Someone shouted at me and I ran toward the exit as I would escape a bad dream. My last visual impression was made by those smooth faced, young men watching me leave. May that impression remain with me until my dying day, for when that train returns many months from today, one third of those seats will be empty."

![]()

The 11th Airborne Division enters Japan (1945) by Hugh D. Cox

I hear this history from an old airborne infantry major in the 1960's who served as a rifleman Private in the 11th Airborne Division at the end of World War II. He had just been assigned to the Division at the time the Pacific war ended with Japan's surrender. His battalion was assigned to fly into an airfield near Tokyo, meet with Japanese authorities, and be transported in vehicles by the Japanese military to Yokohama harbor. Once there, the airborne element would assist harbor personal clear the harbor so large number of occupation troops could be sent into Japan through the harbor facilities.

He was with the first American military unit to enter Japan after the surrender.

Apprehension and fear were evident as this unit flew by C-47's into the Japanese airfield at night . They exited the many U.S. aircraft after landing and secured the airfield. As agreed, the Japanese military had trucks waiting for the several hour trip to the harbor. These airborne soldiers boarded the trucks and began the trip. Weapons were loaded, locked and ready because no one knew what to expect from a nation that honored sacrifice through death in battle.

As the airborne drove into the night through the urban streets all the way to the harbor, they saw hundreds of thousands, if not millions, of Japanese civilians lining the streets on both sides.

No Japanese person faced the street nor looked at the U.S. troops. All had their backs to the street. The Major remembered that no U.S. soldier spoke a word on the trip. They could not see the emotions of the people, but believed many were wailing and crying.

By his profound recollection of the details, I could tell that his experience was one of the most powerful scenes he ever saw. He was also a Korean war combat veteran, but he remarked that his nightmares were most often about the memory of the masses of people with their backs to the first U.S. soldiers to enter Japan.

![]()

|

|

Sergeant Major John Diffin, 82d Airborne Division by Hugh D. Cox

On February 7, 2007, I received a telephone call from Sergeant Major (retired) John T. Diffin who lives at 663 Horseshoe Road, Fayetteville, NC 28303-2522. I admit to some emotion in receiving the call. Sergeant Major is now age 84 and just completed his written history contribution about the 505th Parachute Regiment (of the 82d Airborne Airborne Division). He sounded as articulate, confident and professional as he did 36 years ago. He is still our hero even if he does not accept that title.

When I transferred to the elite 82d Airborne Division in 1970, the Sergeant Major of the G2 section was John T. Diffin of New York. He was quiet and thoughtful man who treated every man in the section as if that man was his son.

Then I learned that Sergeant Major Diffin had parachuted near Arnhem in Operation Market Garden in 1944. He had always been in the 82d Airborne since World War II (except for a short time as a civilian after the war). He also served in the Korean War with the 187th Regimental Combat Team (Airborne) and in Vietnam with the 101st Airborne Division

Although he had a close knit and religious family, Sergeant Major Diffin treated his unit like family and kept the offices and barracks with the same care one would put into one's home.

I had not yet read the book, "A Bridge Too Far" at that time so I did not yet understand the incredible disaster that awaited the British 1st Airborne Division, the U.S. 101st Airborne Division and the 82d Airborne.

His personal demeanor was and is worn with the same quiet pride of his many awards and many heroism decorations.

Sergeant Major Diffin was one of those rare and brave soldiers and professional warriors who survived many of the great battles of major wars. His contribution to the war efforts of three wars transformed world history.

|

![]()

Khe Sanh Khe Sanh Combat Base 1968

My Unexpected Visit

to Khe Sanh Hill 910 in April, 1968 (I now know I was not on Hill 861 as I

previousy thought.)

by Hugh D. Cox

In April 1968, I was a First Lieutenant with Army Special

Forces assigned to MAC-SOG in Vietnam. I was given a mission to fly by Army

helicopter to Khe Sanh to deliver intelligence documents to our Special Forces

unit located within the Khe Sanh combat base.

The North Vietnamese siege of the base had ended and the

U.S. Marines were dismantling much of the base. My flight was a routine one

since the air strip at Khe Sanh was not under constant indirect fire. We flew

over some of the most historic terrain of the Vietnam war including Camp

Carroll, the Rock Pile, Highway 9 before we reached the airspace over Khe Sanh.

When we reached that area, I was astonished to see the

bombing devastation on the hills and mountains surrounding the air strip -

particularly to the West. Miles and miles of B-52 bomb craters pockmarked the

landscape. There were tens of thousands of bomb craters within sight.

As the helicopter descended, the pilot received an urgent

mission to undertake a medical evacuation "medevac" from a U.S. Marine outpost.

The pilot quickly gained altitude and flew north from the air strip to a

mountain ridge about 3,000 feet high. When we approached the ridge, I could see

that it was almost like a knife edge with very steep ridges dropping away from

the long spine of the mountain. The pilot asked me to jump off when we reached

the mountain top ridge. He explained that he needed no extra weight and promised

he would return for me. As the only passenger, I jumped from about 10 feet above

the ridge.

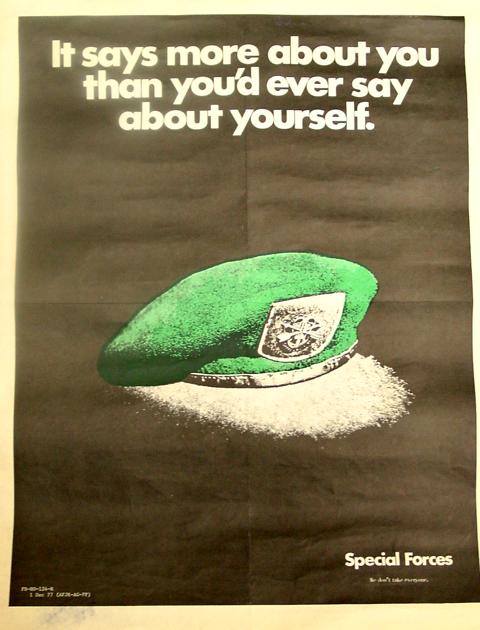

I was on Hill 910 and it was one of those war experiences

one can never forget.

I was not certain how long I was there. Time spent waiting

in a war is irrelevant.

This mountain ridge was manned by elements of 26th Marine Regiment). I saw only a few Marines during my visit.

Several Marines were moving about. Each acted in very

exhausted slow motion carrying canteens, supplies and ammunition back and forth.

Their young faces all had heavy beards and deep set eyes. I simply watched them

as I sat down with my briefcase and weapon. It was as if they had always been

there in filthy, damp and torn uniforms. They moved deliberately in spite of

their distant stares. They seemed so young and I felt so old at age 25. These

Marines were experienced combat veterans deprived of adolescence. They carried

simple things like water and food as if it was for holy communion. Anyone who

saw them on that day in 1968 would be proud to be with them even for a short

period of time.

No one spoke to me. These Marines seemed busy and

unconcerned about my presence. It was as if I had always been there sitting on

the ground in my clean uniform and green beret clutching my briefcase and M16.

Their defensive position along the mountain ridge was one

of the most precarious I had ever seen. These Marines occupied the spine of the

ridge for only about 10 meters down the steep ridges from the top. Then there

was another 10 meters of cut down vegetation probably filled with mines. Beyond,

the heavy jungle loomed just 20 to 30 meters away. The North Vietnamese could

have been upon us within seconds. I looked over the other side of the ridge. The

defensive setup was the same on both sides of the mountain. Hill 910 seemed to

be an invitation to attack.

I thought it was best to wait until I was spoken to. The

Marines knew I was there. Army types know that Marines are different. I

located a foxhole to move to if needed. I tried not to show my growing anxiety.

This strategic combat location was the bloodiest Vietnam

ridge I ever visited. Each attack on the Khe Sanh Hills was a potential enemy victory.

Holding this ridge seemed doubtful to me. I admit I was scared.

I had read the reports of the battles along these

mountains and ridges. Hundreds of Marines were killed or wounded in taking the Hills and the nearby mountain tops like Hill 881 South and Hill 881 North. Brave

NVA soldiers took even more casualties in those battles. In January, 1968, the

Marines had to take the ridge more than once to secure it. It came under serious

attack again in July, 1968 - after my short visit. Once secured in January 1968,

Hill 861 and 910 remained firmly in Marine hands.

Finally after a long period of sitting, I was approached

by one young Marine who asked me how he could transfer to the Army. He seemed

dead serious.

I do not remember my answer. We talked for a half hour in

quiet tones while I constantly scanned the tree line below for enemy movement.

Everyone knew the elite 324th NVA Division was in this

area.

Within a few hours,

the helicopter returned to pick me up.

During my visit, I knew I was among special men, U. S.

Marines, who could

be measured by a simple yardstick of courage and trust. Race, class and family

background meant nothing on that ridge. I was deeply moved by each Marine's simple

act of sharing with his brothers under combat conditions.

Since that day, I always speak of U.S. Marines in very

respectful terms. I will never forget the Corps' finest on Hill 910.

written on September 28, 1999

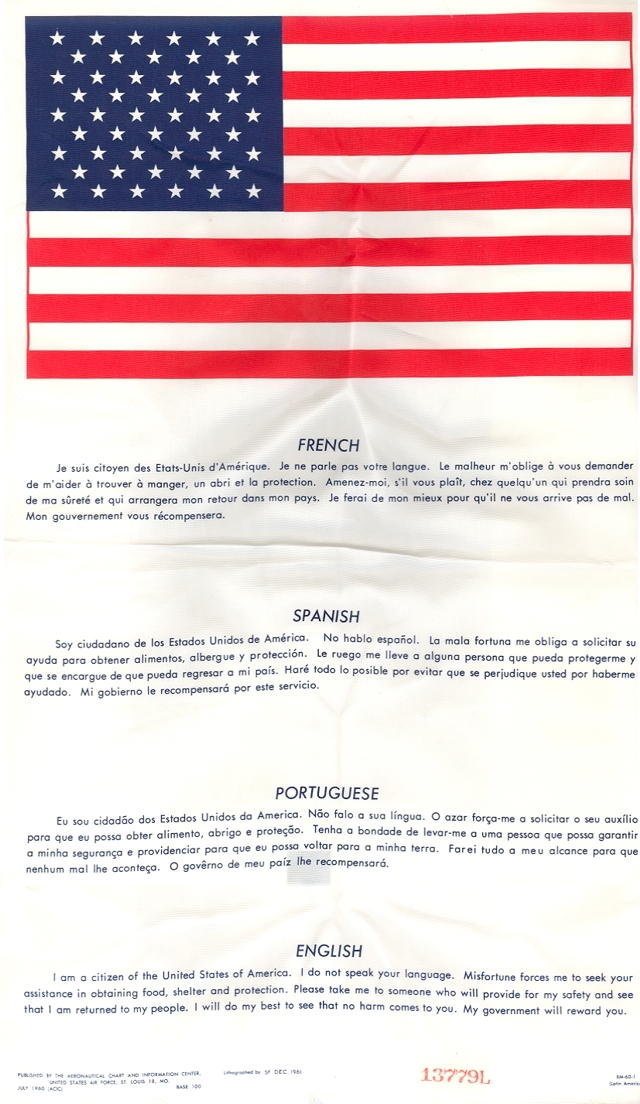

The Blood Chit was used on the British model by United States pilots and air crews who found themselves downed behind enemy lines seeking assistance in escape and evasion. These Blood Chit items were made of silk or other cloth materials. Often worn on the back of a flight jacket, the blood chit was unique to that individual based on the identity number on the chit. Civilians who successfully assisted air crew members were rewarded by the United States Government. Civilians who assisted held the air crew members as captives until positive identification could be made using fingerprints and confirmed by radio transmission. This fascinating history involved a complex evolution for the protection of civilians and air crew members. Below is a "training" blood chit example.

|

![]()